As Bad As It Got: Chelsea

The esteemed football magazine "When Saturday Comes" (reserve your copy from all good newsagents today!) has, for a long time, run a series called "As Good As It Got", in which contributors describe the greatest moment of their club's history. As I am a massive plagiarist, I thought this blog could do with something similar, but I'm not too interested in stories of success. Stories of dismal failure are much more my sort of thing. So, over the next few weeks, I will be bringing you tales of woe, disaster, mis-management and general incompetence - re-tracing the worst moments in the history of some of your favourite (and least favourite) clubs.

The esteemed football magazine "When Saturday Comes" (reserve your copy from all good newsagents today!) has, for a long time, run a series called "As Good As It Got", in which contributors describe the greatest moment of their club's history. As I am a massive plagiarist, I thought this blog could do with something similar, but I'm not too interested in stories of success. Stories of dismal failure are much more my sort of thing. So, over the next few weeks, I will be bringing you tales of woe, disaster, mis-management and general incompetence - re-tracing the worst moments in the history of some of your favourite (and least favourite) clubs.

The thing is this: every club has had a bad period. Every club. Arsenal fans will crow about their unbroken record in the top flight since 1919, but they'll be a little more quiet about how they got there in the first place, or the long period in the 1970s and 1980s when they seemed for likely to be relegated than win anything. It's all relative. For Manchester United, a year outside the First Division in the mid-seventies must have felt like the end of the world. For supporters of, say, Bristol City, it must have been the three successive relegations that they suffered in the early 1980s. How would you cope with such a run? From Anfield and Liverpool to Spotland and Rochdale in less time than it takes to qualify as a doctor? The mind boggles.

In this era when it seems as if the stranglehold of three or four clubs in English football seems likely to last forever, it's appropriate that we start off with Chelsea. Not too long ago, you see, Chelsea were rubbish. They were about the sixth best team in London. They fell agonisingly from grace, and it took them years to recover. It's a salutary tale for those who swan up and down the Kings Road, lording it over the rest of us. The rest of you, sit back and enjoy, but enjoy it with this thought in the back of your minds: there but for the grace go I.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Chelsea were reasonably successful. They won the League in 1955, and got the FA Cup final in 1967, although they lost that to Tottenham Hotspur. They were London's properly glamorous team. Arsenal were somehow too dour. Spurs and West Ham didn't win enough. Chelsea, though, had a great team - Peter Bonetti in goal, Ron Harris leading the back line, and the precocious Peter Osgood leading the front line. Their high water mark came with the 1970 FA Cup final, when they completed Leeds United's appalling end of season collapse by beating them 2-1 after a replay. Raquel Welch and Michael Caine were regular visitors. Their location on the Kings Road allowed them to blend into "Swinging London", but these days couldn't last forever. They did follow up their FA Cup win by winning the European Cup Winners Cup the following year, beating Real Madrid in the final, but their subsequent fall from grace was public, and very, very undignified.

The decline started as soon as the next season. They finished mid-table in the league, but were beaten in the League Cup final by Stoke City, and in the FA Cup by Orient. Their defence of the Cup Winners Cup didn't last very long, either - they were eliminated by the Swedish representatives, Atvidabergs. The problems were not merely on the pitch. Manager Dave Sexton fell out with star players Alan Hudson and Peter Osgood during the 1973-74 season, and both were sold in the summer of 1974. It was a bad move, but was compounded by an even worse one: the decision to convert Stamford Bridge into a 60,000 capacity super-stadium in the middle of a global recession. They got a quarter of it done. Construction of the enormous East Stand, which was for many years the biggest stand in English football was fraught with risk: spiralling costs, material shortages and workers going on strike put the cost through the roof. In the event, it cost three times the £1.6m budget that the club had allowed for it. For the whole of the 1973-74 season, one side of Stamford Bridge was out of use, and the lack of atmosphere, compounded by plumetting crowds, unsettled the players. By the time it was finished, Chelsea were nearly £3.5m in debt. Their financial run was such that they were unable to buy a single player for four years, between 1974 and 1978.

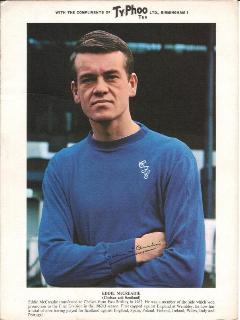

In 1975 they were, perhaps inevitably, relegated, but were promoted back in 1977. Soon afterwards, though, manager Eddie McCreadie (who had replaced Sexton in 1974) quit after the chairman refused to give him a club car, and the brief revival was over. His replacement, Ken Shellito, was another veteran of the team of the early 1970s, kept them up in his first season in charge, but 1978-79 started disastrously for them. The best of the young players that Eddie McCreadie had brought through had to be sold to balance the books, and by the time Shellito quit at the end of 1978, they were well adrift at the bottom of the First Division and heading for relegation again. They fell through the trapdoor again in May 1979, with Danny Blanchflower in charge. This time, there was no immediate return. Crowds continued to decline, and the few decent young players that they had were sold off. Geoff Hurst had a go in charge, but was sacked in 1981, with Chelsea by this time a mid-table second division team playing in front of four-figure crowds. Under John Neal, it looked as if things might improve. In 1982, they pushed Spurs all the way in the FA Cup fifth round, but it was a false dawn, and the following season was their absolute nadir. They were in the relegation places for most of the season, and only an improbable four points from their final two matches kept them up.

Into the middle of this sorry mess had come Ken Bates, who had bought the club for £1 in 1982. My opinion on the Birdseye-like Bates is well known. We can, at least, take solace from the fact that he turned down the offer to buy Stamford Bridge. It would almost certainly be a housing estate now if he had. Bates, a pugnacious man if nothing else, sought to take on the more troublesome elements of Chelsea's support, and his solution to the increasingly frequent pitch invasions at Stamford Bridge was, well, original. He wanted to electrify the fence around the pitch. It should give you some idea of how low the general opinion of English football supporters was by 1982 that the idea taken seriously at all, but even this was a step too far, and the idea was eventually dropped.

With their finances finally starting to stabilise by the summer of 1983, Neal was allowed some money to invest in the team, and he invested wisely. David Speedie, Kerry Dixon, Pat Nevin, Eddie Niedzwiecki and Nigel Spackman were drafted in, and Chelsea were promoted back to the First Division in 1984. Relegated again in 1988 for a season, they were promoted straight back and have been there ever since.

Looking back, it's difficult to imagine being Chelsea being a by-word for managerial incompetence, under-achievement and crisis, but their position between 1973 and 1984 mirrored the state of the English game. Although they were unfortunate in their timing with the reconstruction of the East Stand, it was a sign of the quality of management within the club that they thought that such an ambitious project was a good idea during a time on economic collapse. No single structure has ever come so close to ruining a football club. It's a lesson that Arsenal would do well to heed as I write this. Over a period of over a decade, successive managers contrived to turn one of English footballs most successful clubs into a shadow of its former self.

Next in this occasional series... Manchester United.

1 comments:

Of course, Chelsea's lean spell of the 1980s will look like a regular old Teddy Bears' Picnic when Abramovic finally wins the Champions' League, gets bored and takes his ball home with him.

I'll try not to laugh too hard when it happens.

Post a Comment